Simpler UI Logic With Finite State Machines

Cover photo credit: twinsfisch

Finite State Machines are a pattern that has been around for a long time. The basic idea is that a given component or set of components can only exist in a single state at a time. The state they exist in is based on events that can trigger the component to move between states. The most famous state machine for front-ends is probably redux.

A simple example

The simplest example of this is a toggle switch. The switch state can either be “on” or “off”. The events that causes this state to change is a “toggle” event. Two states, one event, and nothing else.

This applies to a UI very nicely. Let’s take a real world example from Google. The state of the “App Tray” is in a closed state. When the user clicks on it, the tray opens. If the user clicks away from it, or clicks the icon again, the tray closes.

This is exactly like our light switch! Two states, one event. Our two states are “open” and “closed”, and our one event is a “toggle” event that can be fired in a few different ways.

Simplicity is great, but what about complex scenarios

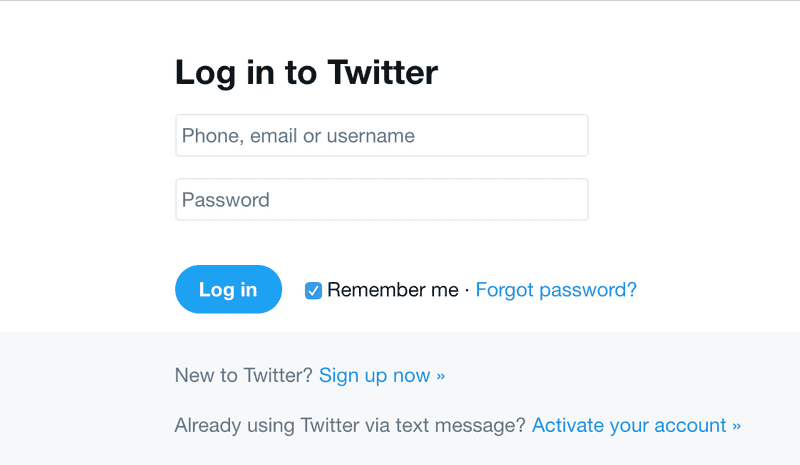

Believe it or not, this is where Finite State Machines really shine! Let’s take a look at a login form:

Looks simple enough, but there are a lot of different states this form can be in:

- Initial State

- Submitted

- Error

- Success

Each of these states has a different representation in the UI, and each of these should be mutually exclusive to the others. It would be a bad day if both the Error and Success states were being displayed at the same time, or worse the loading state isn’t changed when an error occurs.

Let’s look at a typical approach without using state machines:

return

{

!isLoading && !isError && !isSuccess ? '' :

<div class="notification">

{ isLoading && !isError && !isSuccess ? <LoadingImage /> : '' }

{ !isLoading && !isError && isSuccess ? <SuccessMessage /> : '' }

{ !isLoading && isError && !isSuccess ? <ErrorMessage /> : '' }

</div>

}We need to evaluate every flag property in order to render any of them. This works for today, but what happens when we introduce new states like ‘invalid input’ and ‘bad password’? We suddenly have to update every possibility with these new flags to guarantee none of them can be displayed together!

A simpler approach would be to have a single variable for state, and only allows switching between well known states!

Here’s what that could look like:

const STATES = {

initialState: 'initialState',

submitted: 'submitted',

error: 'error',

success: 'success',

isValid: function (possibleState) {

return this.hasOwnProperty(possibleState);

}

};

const state = {

currentState: STATES.initialState

};

changeState(newState) {

if(!STATES.isValid(newState)) {

throw new Error(`Unknown state provided. Provided value: ${newState}`);

}

state = {

...state,

currentState: newState

};

}This code can guarantee that only valid states can be set, and that only one state can exist at a time. What does this really buy us compared to our previous example?

Check out this little bit of jsx:

return

{ STATES.initialState ? '' :

<div class="notification">

{(() => {

switch(state.currentState) {

case STATES.submitted:

return <LoadingImage />;

case STATES.success:

return <SuccessMessage />;

case STATES.error:

return <ErrorMessage />;

}

})()}

</div>

}The handling of notifications for login has been dramatically simplified! No more need for complex logic in our view, just a simple switch case!

Keeping logic away from our rendering code means faster render times, and a much easier set of logic to understand when writing and maintaining that code.

Quick recap

Finite state machines are a great way to simplify our logic for user interfaces. Keeping a single possible state allows us to better manage all of the potential complexity that could otherwise be introduced.